Mammals (Mammalia) are a highly developed and exceedingly successful class of vertebrates. They evolved from extinct reptiles from the Therapsida group. Only mammals have the following characteristics:

- in females, developed mammary glands, in which milk is produced to feed the young,

- hair and

- some special features in the structure of the skull (three auditory ossicles in the middle ear, the lower jaw is composed of one only, i.e. the lower jawbone, which is joined directly with the rest of the skull, the teeth usually differ in shape; heterodont dentition).

Mammals have highly developed large brains, an efficient blood-brain circulatory system with a four-chambered heart, internal fertilization, and are viviparous (except for the Monotremata group of mammals, which lay eggs). Through physiological processes in the body, they produce heat and maintain body temperature at a constant level, independent of the temperature of the environment. This enables them nocturnal activities and life in the most diverse environments. They are distributed on all continents and in all oceans and seas. There are currently over 5,480 known mammal species. Even though they are not as species-rich as many other groups of animals, they are extremely diverse as far as their size, body structure, diet and behaviour and habitat selection are concerned. Among mammals, we can find the largest ever living animals on Earth (the Blue Whale with a length exceeding 20 metres and a weight of up to 160 tons), as well as representatives of some bat and shrew species weighing slightly over a gram and a half. Mammals conquered land, water and air environments. Humans, mammals themselves, threaten them particularly by destroying and fragmenting their habitats, by excessive hunting and the introduction of non-indigenous species. According to the Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2009), at least 25% of mammal species are threatened with extinction. Specifically, at least every fourth species is on the verge of survival.

MILK GLANDS

Mammals are the only animals with mammary glands. Milk is very rich in nutrients, since it contains proteins, fats and carbohydrates. Breastfeeding brings important advantages to mammals: young mammals grow very quickly after birth and have better chances of survival as they have no need to searching for food on their own.

HAIR

Hair is a skin formation and just like fur in most mammals densely overgrows the skin. Getting hair brings several advantages to mammals: fur slows down the exchange of heat with the environment, protects the body against strong sunlight and skin wounds, in aquatic mammals it is waterproof and keeps them dry, it is used for communication (e.g. bristly hair), it enables concealment with a protective colour or colour patterns and helps them defend against predators (spines), while whiskers play an important sensory role.

Bear fur efficaciously retains body heat. It usually appears in shades of brown, less often in yellowish or almost black colours. Longer and fringed hair covers the dense and soft undercoat. Photo: M. Jernejc Kodrič

SKULL

The Fox’s (Voles vulpes) skull. Mammalians have four basic types of teeth: incisors (1), canines (2), premolars (3) and molars (4). The last two types of teeth are collectively called molars. The lower jaw is composed of only one bone (lower jawbone), which is directly connected with the rest of the skull.

LAND, WATER AND AIR ENVIRONMENTS

Land mammals live in most diverse habitats: in open grassy regions, rocky areas, deserts, dense undergrowth, tree canopies, underground burrows, in temporary shelters in the ground, etc.

Water mammals possess a hydrodynamically shaped body. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) off the Slovenian coast. Photo: T. Genov / Morigenos

The Red Squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) spends most of its time in trees, where it also builds its nest. On the ground, It moves with long jumps. Photo: D. Šere

The Alpine Marmot (Marmota marmota) inhabits mountain pastures, where it digs underground dwellings. In them it hibernates, spends the night and takes refuge when in danger. Photo: M. Jernejc Kodrič

HISTORICAL PRESENTATION

The Slovenian Museum of Natural History is a direct descendant of the Carniolan Provincial Museum, founded in 1821, where Henrik Freyer was employed as its first curator (in the 1832-1853 period). He was the first who systematically collected vertebrates in our territory. His collection served as a basis for his Fauna of Carniolan mammals, birds, reptiles and fishes (Ljubljana 1842), which is a fundamental work for our vertebrate species knowledge. He listed 50 species of mammals (“sucking animals”), for some of them providing information on their habitats or even concrete locations. Freyer mounted the animals intended for display. From Freyer’s mammal collection, only two mounts of the autochthonous lynx have survived to this day, although with no appropriate documentation. Apart from mammal exhibition collections, mammal study collections began to appear in the world during the second half of the 19th century. Of each individual specimen in these collections, mainly the skull and skin are held. They are intended for the scientific study of the material and are irreplaceable reference sources. In those times, the founding of study collections did not materialize in our country, and the sphere of mammal collecting and studying stagnated for a long time. In the period between the two world wars, mammals were collected predominantly by foreign naturalists in our country, while our rare naturalists dispatched the material to museums abroad. In its study collection of mammals, the Slovenian Museum of Natural History holds some wild game animal skulls collected by S. Bevk at that time. In the post-war period, mammals were temporarily dealt with in the Museum by S. Brelih and J. Gregori (summed up from: The Mammals of Slovenia, B. Kryštufek, 1991). In 1978, B. Kryštufek embarked on intensive mammal field collecting. The fruit of his collecting and collaboration of museum colleagues and zoologists from Slovenia and countries in the territory of the former Yugoslavia is a rich mammal study collection. The collection also includes material collected prior to 1978, with the oldest specimens dating back to the beginning of the 20th century. On the basis of the study and work in the collection, B. Kryštufek’s book The Mammals of Slovenia (1991) was published, while partially on the basis of the study collection, the Key to classification of vertebrates of Slovenia, Kryštufek & Janžekovič, 1999) was created. This demonstrates the collection’s significance for the basic natural science research in the Slovenian territory. With the aid of material from the study collection of the mammals housed in the Museum, numerous BSc and MSc theses, publications in domestic and foreign professional journals were realized, with collection material also used in the project to establish Natura 2000 networks. In the last few years, the collection has been intensely (re)arranged according to the species taxonomic affiliation and geographical areas. It is digitally catalogued as well, and the Museum is acquiring material for the collection also owing to the adopted legislation on endangered animal species.

SOME INTERESTING FACTS FROM THE MAMMAL STUDY COLLECTION

In the last few decades, the importance of study collections has increased even more due to the rapid extinction of animal and plant species as well as destruction of their living environments. Study collections are all over the world thus keeping numerous mounts of currently already extinct or endangered species, which unfortunately happen to be the last evidence of the existence of the species, and at the same time all the material available for research. Suitable mounting and preservation of these specimens is therefore of utmost importance.

In our study collection, too, some endangered and rare mammal species are kept:

The Lynx is one of the most endangered animal species in our country, for it is currently yet again on the verge of extinction (it was exterminated in the 19th century, but reintroduced here in 1973 by the Hunting Association of Slovenia). The most probable causes of the drastic population decline are inbreeding (the entire population originates from just a few reintroduced animals) and illegal hunting, with its habitat destruction, lack of prey, etc. probably adding to it.

The Balkan Snow Vole is a rare and endangered rodent species. It is endemic to the western part of the Balkans and on the way of extinction. This species can very rarely be found in natural history museums abroad; The Slovenian Museum of Natural History holds more study material of this Vole than all other museums combined. At some localities, from which the stored material was obtained, the species has become extinct in the last few decades.

The Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) was exterminated in the Slovenian territory in the 17th-18th centuries. As a consequence of its introduction in Croatia, it naturally settled in Slovenia. Hence, it has been with us again since 1998. In our study collection, we keep few skulls as well as complete skeletons of this species.

The Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra), which is currently fairly rare in our country, but was widespread in the past, was mercilessly persecuted by man, with water pollution also having a strong influence on the decline of its population.

The European Hamster (Cricetus cricetus) is already highly endangered owing to environmental changes in Central and Western Europe. In Slovenia, it is widespread only in the vicinity of Središče ob Drava. In our study collection, two specimens from Slovenia are held.

Type specimens are of great scientific value in our study collections. On the basis of these specimens, taxa are described and named, e.g. new species and subspecies. They are therefore documents of the taxa and are used as reference material for determination.

A few albino mammal specimens are also held in our study collection. Albinism is a hereditary lack of pigment in the skin, hair and eyes.

Only a few examples of non-European species of large mammals are held in our collection.

The Balkan Snow Vole's (Dinaromys bogdanovi) skull from dorsal and lateral sides. Photo: T. Klenovšek

The skull of the Eurasian Beaver found in 2005 in the Sotla River tributary near Podčetrtek (left), and the skull of the same species run over in 2006 at Dobruška vas (right). Photo: C. Mlinar Cic

THE MAMMALS OF SLOVENIA

Our mammals are taxonomically classified into eight easily distinguishable orders (Wilson & Reeder, 2005): hedgehogs (Erinaceomorpha), shrews, moles and flatworms (Soricomorpha), bats (Chiroptera), rabbits and pikas (Lagomorpha), rodents (Rodentia), whales (Catacea), carnivores (Carnivora) and even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla). Orders are divided into lower systematic categories, families, genera and species. The number of species in our country ranges from approximately 85 (The Animal Kingdom of Slovenia, 2003) to 93 (Key to classification of vertebrates of Slovenia, 1999). Some species stray into our country extremely rarely (e.g. most whales) or have been observed only once (e.g. Common Raccoon Dog: probably as a consequence of being introduce), while certain species develop only temporary populations in nature (e.g. escapes from artificial breeding).

THE REPRESENTATIVES OF OUR ORDERS OF MAMMALS

Mammal vocalization

Rutting, or the mating period of deer, starts in our country in September. Males compete for females emitting their characteristic voices. A male marks its mating territory, announces its social status and attracts females with very loud guttural sounds.

Members of the wolf pack communicate with each other via scent messages, facial expressions, body posture and vocalization. The well-known wolf howling has several meanings. By howling, they announce ownership of the territory, maintain mutual contact when scattered around, or when calling each other before or after a joint hunt. The wolves’ howling can be heard up to 10 km away.

The bats’ high-frequency echolocation calls are inaudible to human ears. We can listen to them with the aid of a special electronic device called ultrasound detector. In this way, we can determine the presence and species of a bat, since echolocation calls differ between species. On the audio recording we can hear the echolocation calls of a Common Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) approaching its prey. In order to determine the prey’s location as precisely as possible, the number of calls emitted in the last moments of the hunt is greatly increased, while the duration of each becomes shorter.

The autochthonous Balkan Lynx

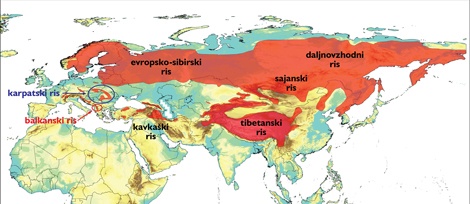

The Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx) is a medium-sized cat, one of the four species of the genus Lynx. It is distributed over vast regions of Eurasia, while its habitat in Europe is fragmented.

There are several lynx subspecies (geographical races). The Balkan subspecies (Lynx lynx balcanicus) is represented by a small number and is endangered as well. It developed during the Glaciation Period in the seclusion of the Balkan Ice Age refuge.

The lynx status according to the criteria of the Red Book of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN):

- the Eurasian Lynx is globally not an endangered species (IUCN Category LC)

- at the European level, the lynx is a potentially endangered species (IUCN Category NT)

- in the Mediterranean region, the Eurasian Lynx is an endangered species (IUCN Category EN)

The Balkan Lynx is stands out from other lynxes by its smaller stature and genetic profile.

The most in-depth review of the Balkan Lynx was published by Dr Đorđe Mirić, late curator of the mammal collection at the Belgrade Museum of Natural History. Photo: Archives of the Belgrade Museum of Natural History

Distribution of the Eurasian Lynx

Photo: Macedonian Ecological Society – Balkan Lynx Recovery Programme

SLOVENIANS ABOUT THE BALKAN LYNX

In the past, much has been written by Slovenians about the native Balkan Lynx, with some important works on the subject created in the Slovenian Museum of Natural History.

Henrik Freyer (1802-1866), the first curator in the Carniola Provincial Museum (now the Slovenian Museum of Natural History), collected material for the vertebrate fauna of Carniola at that time and published his observations in 1842. In this work, he listed the lynx for the Dolenjska region.

Fran Kos (1885-1956) worked as curator and later as Director of the Museum’s Natural History Department. His work “Lynx in the territory of ethnographic Slovenia” (1929) is the most in-depth study of the animal species’ extinction in Slovenia. Later, researchers of indigenous lynx in Southeastern Europe used this work as reference. Kos also reconstructed the most probable origin of two Museum’s lynx specimens.

Fran Erjavec (1834-1887), the prominent Slovenian naturalist, wrote as early as 1869 that the lynx is a permanently occurring beast of the Notranjska forests. Nevertheless, the three lynx killed “in the winter of 1855” in the Borovnica forests, seen by Erjavec himself, are the last unquestionable testimony of this species in Slovenia.

In the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, several Slovenians found a chance of survival in the southern areas of the country, where transferred to various reasons. Some were hunters and naturalists at heart. They left us an extremely important testimony about game hunting in the then Vardar Province, which included the entire modern-day Macedonia with neighbouring parts of Kosovo and southern Serbia. One of them was Tone Kappus.

Tone Černač (1905-1984), a Slovenian from the Primorska region and member of the revolutionary underground organization TIGR, escaped with his family from fascist Italy and worked as a forester at Kačanik on the northern slopes of Šar planina mountain shared by Kosovo and Macedonia. As a good hunter, he helped the locals protect the sheep against wolves. On 21 September 1940, while on duty, he shot a lynx, which he thought, in darkness, was a wolf. At the outbreak of war, he returned to Slovenia on foot and joined the Ribnica Partisan Company at Travna Gora.

THE BALKAN LYNX IN NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUMS

The Balkan Lynx was exterminated by man in the 19th century in a wider area of the Lynx’s former range. Nowadays it is rare in nature, limited to a small area only.

Owing to its rarity in nature, the Balkan Lynx is also scarce in natural history museums. Most of the museum specimens originate from the present day distribution area, but were collected in the previous century.

The Museum’s two mounts of the native Balkan Lynx from the first half of the 19th century are in urgent need of restoration. For starters, we X-rayed the mounts’ interior, and were surprised to find a skull in both mounts; the smaller specimen even had all long bones of the limbs preserved. Bone tissue is an excellent source of “ancient” DNA, which will be able to answer the important question about the identity of the lynxes that were exterminated in Slovenia in the second half of the 19th century.

THE BALKAN LYNX IN NATURE

The Balkan Lynx has survived only in some remote montane regions on the border between Macedonia and Albania, as well as in neighbouring areas of Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro. Its total population is estimated at about 100 individuals which, however, is certainly not enough for its long-term survival.

In 2006, Macedonia and Albania agreed to bilateral cooperation in the Balkan Lynx’s conservation. The 2nd phase of the project terminates this year. For the first time in history, the project collaborators photographed a Balkan Lynx in nature with photo traps. They also embarked on telemetric monitoring of animals and on development of a conservation strategy.

More information on the project

News about the project can be found on the online paper Program ohranjanja balkanskega risa (Balkan Lynx conservation programme).

CARPATHIAN LYNX IN THE BALKANS

The Hunting Association of Slovenia implemented, on 3 March 1973, a project to reintroduce lynx to Slovenia. The project, which was initiated and financed by Karl Weber, a Swiss citizen, was expertly managed by Janez Čop, BSc in Biology. Three males and three females were released at Kočevski Rog. The introduction turned out to be extremely successful, for the lynx spread right across the Dinarides and all the way to Montenegro.

The lynx is only a step away from extinction once more. The only possibility for the survival of its population is a quick import of lynxes from abroad.

Before released into the wild, the lynxes had been kept in quarantine for some time. Photo: J. Gregori

Karel Weber, the initiator of lynx reintroduction to Slovenia (source: Lovec magazine, LXXIX. volume, No. 4/1996.)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND COLOPHONE

Acknowledgements

The Slovenian Museum of Natural History wishes to thank various individuals, associations and institutions for providing information and photos for the present exhibition:

Dime Melovski, MSc, and all members of the project Balkan Lynx Recovery Programme carried out within the framework of the non-governmental Macedonian Ecological Society, contributed photos of the Balkan Lynx from its natural environment and information on the project;

Other photos were contributed by:

Dr. Ferdinand Bego from the Museum of Natural History Sciences, Tirana;

Janez Černač, MSc, Kočevje;

Milan Paunović, MSc from the Natural History Museum, Belgrade;

Dr Svetozar Petkovski and Dr Vesna Sidorovska from the Natural History Museum, Skopje;

Janez Gregori and Ciril Mlinar from the Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Ljubljana;

Editorial Office of the Lovec magazine allowed us to use photos of the lynxes introduced to Slovenia;

the background of the panels is adopted from Janez Černač’s painting (»Lynx’s footsteps in the snow«; acrylic on canvas);

Prof Dr Bojan Zorko, Asst Prof Dr Modest Vengušt and Fahrudin Botonjić from the Veterinary Faculty of the University of Ljubljana carried out X-ray imaging of the mounts;

Exhibiting of two specimens was made possible by:

Dr Romana Erhatič Širnik from the Technical Museum of Slovenia (mount of Carpathian Lynx)

Matija Križnar, MSc, from the Slovenian Museum of Natural History’s Department of Geology (lower jawbone of a lynx discovered at Ljubljansko barje)

During the opening of the exhibition, Janez Černač, MSc presented the skull of an indigenous Balkan Lynx from Šar planina to the Museum of Natural History of Slovenia. We are particularly grateful to him for this important enrichment of the Museum’s mammal collection.

Exhibition colophon

Authors of the exhibition: Prof Dr Boris Kryštufek, Mojca Jernejc Kodrič

Authors of the photos: Prof Dr Ferdinand Bego, Archive of Janez Černač, MSc, Janez Gregori, Macedonian Ecological Society / Balkan Lynx Recovery Programme, Ciril Mlinar, Milan Paunović, MSc, Dr Svetozar Petkovski, Dr Vesna Sidorovska

Preparative arrangement of cartographic bases: Peter Glasnović

Layout: Mia Sivec

Print: Mojmir Štangelj

Implementation: Technical Service of the Slovenian Museum of Natural History

Jackals in Slovenia

In Slovenia, the Jackal’s range has been both expanding and contracting over time. As far as we are able to judge from historical documents, the Jackal was probably constantly present in recent centuries in a narrow strip of the Balkan Peninsula, driven there by the much more widespread wolf. In the 20th century, it gradually spread from southern and central Dalmatia to northern Dalmatia, and in the early 1980s it began to occur quite regularly in Istria. This wave of expansion that also reached Italy and Central Europe (Austria, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia) subsided some time later. Around this time, the Jackal also began to spread in the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula (Bulgaria, eastern Serbia) and in the Pannonian Plain, where the majority of European Jackals live today.

The first vagrant Jackals reached Slovenia as early as 1953, most likely as followers of nomadic shepherds who brought a large flock of sheep to our country from Macedonia in the dry year of 1952. When all sheep were sold, the Jackals dispersed and even reached Kobarid. In the last 20-30 years, they have been occurring sporadically in various areas of the country, but have in western and central Slovenia already acquired the status of species of high constancy that breeds here as well.

The mount of the European Jackal culled in January 2010 in Croatia. The skin was seized during an attempt to bring it to Slovenia on the grounds of violation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Photo: C. Mlinar Cic

ABOUT THE JACKALS

The Golden Jackal is a medium-sized representative of the dog family. Physically, it is similar to a wolf, yet smaller. Its back and tail are reddish-brown with yellow shades, its coat has individual black hairs standing out. The belly is dirty white. Generally, its colouration changes subject to age and season. It weighs up to 16.5 kg, with males by about one tenth heavier than females.

Jackals are easily adaptable animals, using diverse food sources in a wide variety of habitats. They live in savannas, semi-deserts, steppes, forests, mangroves, swamps, maquis, as well as in agricultural and semi-urban areas. The Golden Jackal’s wide range extends from northern and eastern Africa and southeastern Europe, the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East, via southern Asia to Thailand and Burma.

The jackal is an opportunist in terms of its diet. In Europe, it feeds mostly on carrion and slaughterhouse waste of domestic animals. Although it also eats plant food and hunts for smaller vertebrates (rodents, frogs, etc.) and insects, this constitutes only a small part of its diet.

Generally, jackals live in pairs or within family communities (families) that consist of an adult male and female and their young of different generations. Where food is plenty (e.g. in garbage dumps near human settlements), jackals can gather in large packs of up to 20 individuals. Strong bonds are established between family members, with the female and the male living in a long-lasting partnership. They raise young together, mark and defend their territory, often look for food and hunt prey together. Even though becoming sexually mature at eleven months, the cubs often remain with their parents as helpers until the age of two.

"Jackal’s portrait": Like the majority of dogs of the canine family, jackals are characteristically equipped with upright ears and a pointed muzzle. Photo: J. Lanszki

The range of the Golden Jackal (source: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. www.iucnredlist.org)

In Europe, the Jackal survives mainly on the account of slaughterhouse waste. The picture depicts stomach contents with remains of a slaughtered pig. Photo: D. Ćirović

European Beavers are back in Slovenia

THE BEAVER IS CHANGING THE ENVIRONMENT

BEAVER-LIKE RODENTS

In its physical appearance, the Beaver is resembled by two other rodent species, the Nutria and the Muskrat, which are also well adapted to the aquatic environment. They are often confused with beavers, particularly when swimming. At first glance, however, they differ from the Beaver by size and tail. The muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) is with its weight of 1,5 kilograms and body and head length of up to 350 mm much smaller and lighter than the Beaver. It has no web on the toes of its hind legs and its feet are fringed with partially webbed bristles. The Nutria (Myocastor coypus) weighs up to 10 kilograms and measures up to 635 mm in length. Unlike the Beaver, which has the web spread between all five toes of its hind feet, the Nutria lacks it between the toe and forefinger. It has an oval-shaped tail, whereas in the Muskrat it is laterally and in the Beaver dorsally- ventrally flattened.

While the Nutria originates from South America, the Muskrat comes from North America. Both species, however, were introduced to Europe by humans owing to their high-quality fur. In our country, the Nutria was one also bred on farms, and this in few colour varieties, including albino. The nutrias that escaped from captivity have established free-living populations in some places.

THE BEAVER'S RETURN TO SLOVENIA

- In historical times, the Beaver was widespread in Slovenia.

- In the 17th-18th centuries, it was exterminated by man.

- In 1992, M. Jež (Institute for the Protection of Natural and Cultural Heritage, Maribor) launched an initiative to reintroduce the Beaver to Slovenia.

- The initiative, however, did not materialize owing to lack of funds. In the 1996-1998 period, the Faculty of Forestry of the University of Zagreb introduced to the Posavina region 85 beavers caught in Bavaria.

- As a consequence of its introduction to Croatia, the Beaver naturally settled in Slovenia in 1998.

- It first occurred here on the Krka and Radulja Rivers and has been constantly present in this area since 1998. In 2002, it found its home in the Dobličica as well.

- In the winter of 2003/2004, it settled In Bela Krajina and on the Upper Krka River. In recent years, it also reached the Mura and Sotla (2005), and the Drava (2006). In Slovenia, the Beaver is in the initial phase of colonization. The beavers living in Slovenia represent the periphery of the Croatian population.

The historical presence of the Beaver in Slovenia, as evident from its bone remains, historical elements and toponyms (geographical names presumably derived from its name). 1 - Pleistocene; 2 - Holocene (until the Roman era and undated); 3 - historical records from the 17th and 18th centuries; 4 - toponyms. Source: Scopolia, no. 59, 2006.

THE BEAVER'S FUTURE IN SLOVENIA

The Habitat Directive, which is binding for Slovenia, lists the Beaver is in Appendices II and IV. Our Ministry of Natural Resources and Spatial Planning is liable to provide the species with favourable conditions for its long-term existence via the establishment of Natura 2000 areas. The basic biological and ecological requirements of the Beaver in terms of its habitat are:

- Water bodies should be present all year round, at least 0.5 m deep and preferably wider than 2 m and with a constant water level. Favourable habitats are stagnant water bodies (lakes, ponds) with varied topography (small islands, bays, swampy branches). This enables the Beaver a better nutrient base as well as the development of the system of several small territories.

- Woody or herbaceous vegetation must be present all year round. Food should be made available close to the bank (up to 6 m) and less than 400 m from the lodge. The most important trees are willows and aspen. Poplar, birch, hazel, cherry and oak are also suitable. Beavers do not feed on elder.

- The habitat should be linked with other suitable habitats by waterways, which enables the migration of young beavers and the relocation of the colony in the event of the nutrient base being used up.

- The habitat should preferably be in a protected area. The inceptions of the beaver strategy for the long-term conservation in Slovenia are the following: The Beaver is a key species in the ecosystem where it maintains as well as regulates the water system and wetlands through its activities. Its presence and activities increase the ecosystem and species diversity. In Slovenia, the beaver is in the initial phase of colonization, hence no rapid population increase can be expected. The recolonization of Slovenia will be a slow process. At this stage, each family should be allowed to settle down and implement its reproductive potential.

The Fox

THE MASTER OF ADAPTATION

The Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) belongs to the canine family and to the order of carnivores. It has always been known as a cunning and resourceful animal. It is extremely adaptable, both with regard to diet and habitat selection, and has the widest distribution among all animals in the world. It inhabits nearly the entire Northern Hemisphere (Europe, most of Asia and North America), North Africa, and was introduced to Australia by man. It can be found in most diverse habitats; from forests, tundra, prairies and deserts to urban areas. In Slovenia, it is widespread from the coast to the Prekmurje region, while in the mountains it occurs up to the forest line, here and there even higher. It feels best in landscape where forests, meadows and cultivated areas intertwine.

THE RED FOX’EXTERNAL FEATURES

Its body is elongated and slender, and her legs are fairly short. It has a long and bushy tail, a pointed muzzle and large, erect and very mobile ears. The fur is reddish-brown on the back and dirty white on the belly. The tail is usually embellished with a white tip, the back of the ears and partly the legs are black. Other colour varieties of the fur are also known (e.g. “silver”). Its winter fur is denser and with more pronounced shades of grey. The Red Fox weighs 4-8 kg, the length from the head to the trunk is 45-90 cm, and the tail measures 30-50 cm. Males are larger than females.

FROM THE FOX'S LIFE

As far as diet is concerned, the Red Fox is not fussy at all. It preys particularly on rodents such as voles and mice, although its menu also includes rabbits, various invertebrates (earthworms, insects), carrion, reptiles, fish, frogs, birds and eggs. In different areas and seasons, It also likes to reach for berries and fruits, as well as organic waste in human settlements… Generally. foxes eat only what’s offered to them by the environment. The Red Fox is well equipped for prey hunting prey; it is fast, has excellent hearing and sense of smell. It hunts rodents with a characteristic fox jump; it flies high into the air, and upon landing grabs the prey with its front paws. This animal buries excess prey and very well remembers this kind of “storehouse”.

The Red Fox is active mostly at dusk and night, but can also be seen during the day. It digs its own den or occupies badger burrows, and scent-marks its territory: urine, feces and secretions from the scent glands. It spends most of the year in solitude. Foxes communicate with scent marks, vocalization and even body posture. They mate in winter; the female is pregnant for slightly over 7 weeks. In spring, she usually gives birth to 4 to 7 helpless cubs and rarely leaves them during the first three weeks, with the male bringing the food. When the cubs are one month old, they leave the den for the first time, and in the autumn of the same year become independent. The lifespan of foxes in the wild is on average three to four years, in captivity even up to twelve years. Its natural enemies are wolf, lynx, dog and the Golden Eagle. Foxes are among the main carriers as well as victims of rabies and can also infect other mammals, including humans.

THE FOX AND MAN

As a proverbially cunning animal, the Fox appears in many world and Slovenian tales, fables, fairy tales and songs. Despite its popularity, humans do not spare it. It has been persecuted and hunted for centuries, in times past mainly for its fur and being a “pest”, and in the last few decades also as a rabies carrier. It is all too often forgotten, however, that it is also a very useful animal, considering that it regulates the rodent population and “cleans up” carrion and sick animals.