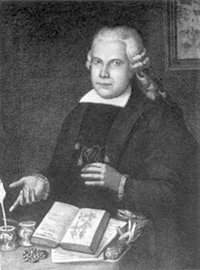

Joannes Antonius Scopoli

The Founder of Modern Natural Science in Slovenia

In 2023, 300 years will pass since the birth of the naturalist Joannes Antonius Scopoli (1723-1788). Between 1754 and 1769, he worked as the first doctor for miners in Idrija. Besides studying the diseases and social conditions associated with the mining profession, he devoted much of his time to exploring the environment of Carniola. He produced catalogues of plants, fungi and animals and published works that propelled Carniola (and thus Slovenia) into the ranks of global scientific superpowers. He named new species in accordance with the principles that are still observed in modern natural sciences. He was a true polymath, studying such diverse fields as mineralogy and paleontology, agronomy, veterinary medicine, medicine, pharmacy, chemistry and forestry.

Joannes Antonius Scopoli was born on June 13, 1723 in Cavalese in South Tyrol. He first attended school there, but later continued his education in the towns of Trent and Hall near Innsbruck. He studied medicine in Innsbruck and graduated in 1743 with a thesis On the Diet of Intellectuals. After graduation, he served his apprenticeship at local hospitals in Cavalese, Trent and Venice. In the following couple of years, he found employment as the personal secretary of the bishop of Seckau, Leopold Ernst von Firmian, while preparing for the medical exam in Vienna, which would grant him the state licence for general medicine practice. In 1754 protomedic Gerard van Swieten sent him to Idrija to take up the newly established position of miners’ doctor. He found his situation there quite untenable and quickly fell into dispute with the mine administration. His troubles culminated in 1763, when he asked the empress Maria Theresa for a transfer, but since she wanted to keep him in Idrija, she offered him the position of professor at the newly established mining school, where he could teach chemistry and mineralogy. Scopoli stayed until in 1769 he obtained the position of mining councilor and professor of mineralogy and metallurgy at the mining academy in Banská Štiavnica. In 1776, he was offered the position of professor of chemistry and botany in Pavia, which he accepted. During his time in Pavia, he wrote textbooks for both subjects, maintained a mineralogical cabinet, as well as several collections of mollusca, and founded a botanical garden. He died on May 8, 1788.

Joannes Antonius Scopoli (1723–1788).

During his years in Idrija, Scopoli realized that this part of the monarchy is inhabited by many previously undiscovered fungi, plants and animals. Impressed by the natural wonders of Carniola, he eagerly conducted research into the surroundings of Idrija and began to systematically list plants, fungi and animals. Following the example of Carl Linnaeus, he named them in accordance with the modern natural science method and thus could be viewed as having laid the foundations for many scientific branches in present-day Slovenia. During his travels, he also turned his attention to the characteristics and problems of Carniola’s agriculture, animal husbandry and forestry. He proposed solutions to reduce the workload of the locals and encouraged them towards a more sustainable use of natural resources. Similarly, contact with the people of Carniola also turned out to be a rich source of knowledge for him. He wrote of their traditional use of plants and fungi and described the locals’ method of beekeeping.

Through systematic research, observation and collection, Scopoli, his contemporaries, and his successors laid the foundations for many natural history collections and, through various publications, spread knowledge of Europe’s natural heritage throughout the continent. Their work inaugurated the mission of present-day natural history museums, which is to collect, preserve, study and present our common natural heritage to the public. They were prolific proponents of the naturalist mentality in Carniola, which culminated in 1821, when the Regional Museum for Carniola was established.

In the year of Scopoli’s anniversary, the Slovenian Museum of Natural History is organizing several events in his memory. There are also events planned on our social networks, so follow us closely.

In the year of Scopoli’s anniversary, we prepared the present film, which presents some of the organisms that were the first to be scientifically described by this tireless naturalist.

Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides Scopoli, 1769

Dalmatian Broom Genista sylvestris Scopoli, 1772

Broad leaved Lime Tilia platyphyllos Scopoli, 1772

PUŠČAVNIK Hermit Beetle Osmoderma eremita Scopoli, 1763

Puščavnika je kot prvi leta 1763 opisal Scopoli po primerkih s Kranjske. Z molekuarno študijo primerkov iz več populacij vrste v Evropi je italijanski entomolog Paolo Audisio s sodelavci leta 2007 pokazal, da Scopolijevega puščavnika tvorijo kar štiri različne vrste. ...

ROBATA STISNJENKA Narrow Mushroom Headed Liverwort Marchantia quadrata Scopoli, 1772

Three toothed Orchid Neotinea tridentata Scopoli, 1772

Hop Hornbeam Ostrya carpinifolia Scopoli, 1772

Field Macewort Mannia triandra Scopoli, 1772

Salad Burnet Sanguisorba minor Scopoli, 1772

Alpine Accentor Prunella collaris Scopoli, 1769

Scopoli's Weevil Otiorhynchus gemmatus Scopoli, 1763

Ground Beetle Carabus catenulatus Scopoli, 1763

Villous Viper's Grass Scorzonera villosa Scopoli, 1772

Caesar's Mushroom Amanita caesarea Scopoli, 1772

Little Crake Zapornia parva Scopoli, 1769

Wasp Spider Argiope bruennichi Scopoli, 1772

Rock Buckthorn Frangula rupestris Scopoli, 1772

Little Owl Athene noctua Scopoli, 1769

Six spot Burnet Moth Zygaena carniolica Scopoli, 1763

Pseudohydnum gelatinosum Scopoli, 1772

Scarlet Flat Bark Beetles Cucujus cinnaberinus Scopoli, 1763

Parasol Mushroom Macrolepiota procera Scopoli, 1772